On the table in front of 27-year-old Rosa Camaja is a basket of black beans, and colourful plastic bowls containing ripe tomatoes, eggs and dried sweetcorn. There are also a couple of coconuts and bunches of yellow bananas. The table is on the veranda of Rosa’s house in the

village of Chitomax, close to the Rio Negro north of Guatemala City.

“Since I’m the only one who lives in the village centre, I’m responsible for selling what I and the other farmers in our cooperative harvest,” says Rosa Camaja.

Rosa belongs to the Maya Achi indigenous people. They have lived in this area a long time, working the land along the river. Thirty years ago, a hydro power station was built, which means the water now collects during the rainy season and covers the fields. Rosa sometimes even has to get around by canoe. In the summer, the fields are dry and infertile. Many people in the area were forced to abandon their farms when the dam was built.

“We didn’t use to care about the land, we abandoned it. In the summer the plants died in the drought, and in the winter everything flooded,” says Rosa.

The farmer’s organization made it possible to work all year around

Supported by the farmers’ organisation Asociacion de Forestería Comunitaria de Guatemala Utz Che’, known as Utz Che’, Rosa and other farmers in the village installed a solar-powered irrigation system in recent years. This makes it possible to work the land also in the dry season. Rosa grows beans, maize, tomatoes, the gourd plant chayote and a flowering herb called loroco.

“We only need to buy sugar and soap, everything else we need is harvested from our fields. If we want meat, we slaughter a chicken or occasionally buy beef,” Rosa explains.

“We didn’t use to have enough food and there were days we went hungry. But now, when I look at the food I have to cook in the kitchen, it makes me so happy. It motivates me to keep on working so we can all eat. That’s our right. Our sons and daughters have the right to eat well and be healthy,” she adds.

Many children in Guatemala are stunted

Almost half of all children under 5 in Guatemala are stunted – the highest proportion of stunted children per capita in Latin America, and one of the highest in the world. The problem is most evident among the country’s indigenous peoples. Women, who are generally responsible for the family’s food provision, represent only a small percentage of Guatemala’s farmers. As in the rest of the world, women in Guatemala often have poorer access to land, funding, education, seeds and fertiliser than male farmers.

Before I joined our support group for women in business, I was a very sad, quiet woman.

A driving force for gender equality and empowering women

Rosa has been a member of Utz Che’ for five years, and today she is a driving force in the village for farming and gender equality. She is one of Utz Che’s guides, who visits families in the village to talk about women’s rights and the division of household chores.

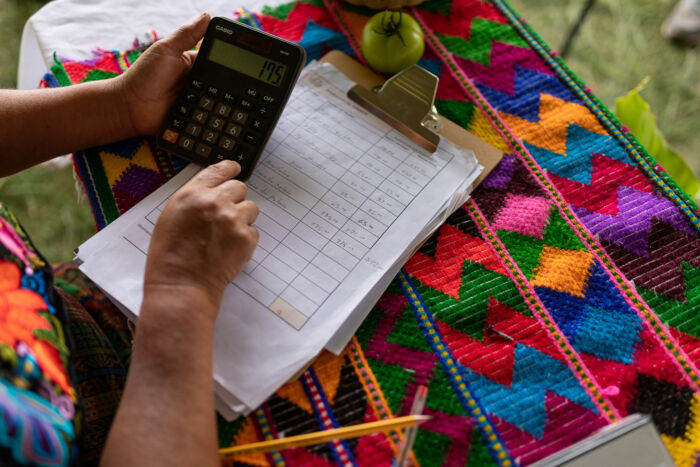

The aim is to strengthen women’s empowerment and voice in important decisions, and in family-run enterprise. The shop that Rosa and the cooperative run is the first one in the village. The cooperative also sells tomatoes to wholesalers in the nearby small town of Cubulco, and they are planning to start up a chicken farm for egg production once they have saved up enough. Rosa’s role in the operation brings her an income equivalent to almost €60 a month, and she regularly saves for the future in the savings and loan group run by the cooperative.

“I’m a different woman today. I make my own decisions, I save money, I have an income from my farm and my family eats well,” says Rosa.

“We are grateful for the food the land provides,” she adds.

The government in Guateamala introduces healthy school meals

To fight stunting in children in Guatemala, in 2017 the government adopted a new law to introduce healthy school meals for all children. For many children, the school meal is the most important meal of the day, and when the schools are closed during the Covid-19 pandemic, child undernutrition risks rising. The law also stipulates that half of all produce for school meals must be purchased from the country’s 2.5 million smallholder farmers like Rosa.

“We women in the cooperative are now working to get the government to buy our high-quality produce for school meals, so the children can eat natural foods produced here in the village, with no chemicals,” says Rosa.